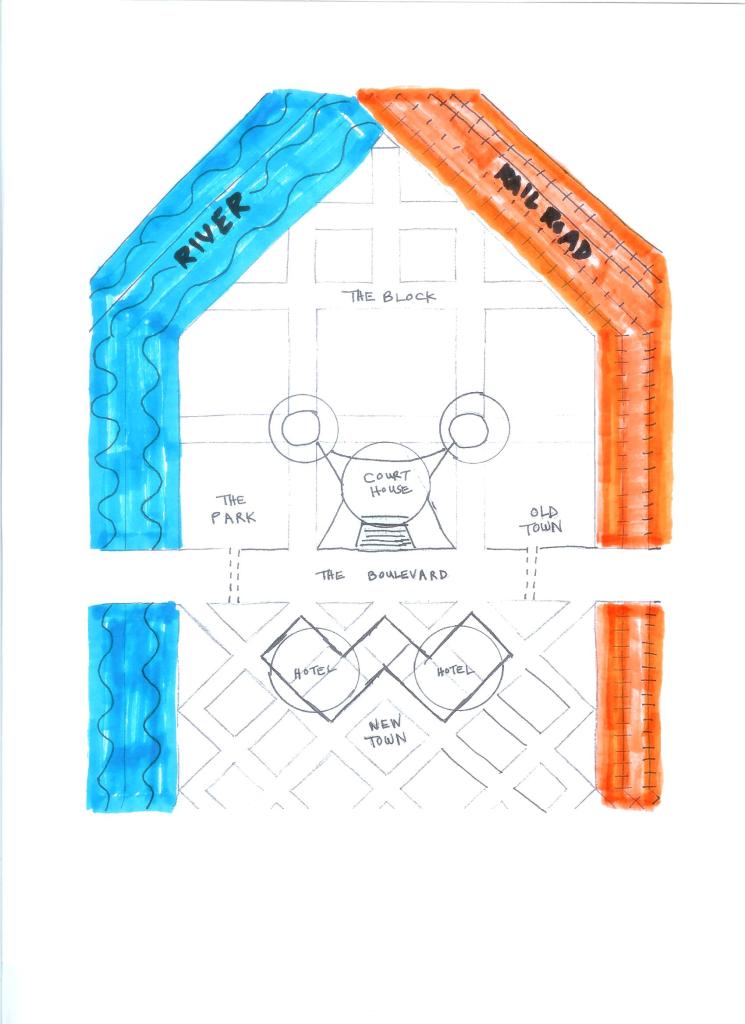

chapter 9: the block

The boy walked slowly on the crowded, neon-blinking street. A swirling, crisp December wind from the River blew newspapers, food wrappers, and paper cups out of the alleys, through the gutters, and up the street. The child passed a peep show storefront—16 PRIVATE BOOTHS—NO WAITING—ALL NEW FILMS—ADULTS ONLY. Brassy music, raucous and blatant, blared from the open doorway of the strip show bar next door. A large number of soldiers and firemen in red windbreaker jackets wandered the street, talking, joking, and bargaining with knots of women, in twos and threes, in the recessed doorways of closed businesses and abandoned buildings.

“Hey, honey, you looking for a date?” asked one girl.

“How much you get?” said a soldier.

“How much you usually pay?”

“Most girls back home do it for nothing.”

“Yeah, honey, but they don’t do it like I do it.”

“How do you do it?”

“How much do you want to pay?”

“Don’t want to pay nothing.”

“Well, that’s what you’ll get then, asshole. — How ‘bout you, sweetheart? Yeah, you! Next to Bigmouth. Does he do all the talking for both of you? Come on over here and talk to me. That’s right! That’s right! Tell your sweet mama all about it.”

The boy passed an ADULTS ONLY bookstore, and at the next storefront, waved to an old woman sitting alone at a table on which a single candle burned. She looked up from the cards spread out before her on the table. Her sign—GYPSY FORTUNETELLER—FORTUNES FORETOLD BY CARDS OR PALM OR CRYSTAL BALL—MADAME ZELDA SEES ALL, KNOWS ALL—leaned awkwardly against the partially open doorway of her shop. A small sign in the next store advertised—FOR SALE: EROTIC APPLIANCES AND OTHER EXOTIC RUBBER PRODUCTS—GUARANTEED TO PLEASE REGARDLESS OF PREFERENCE.

The old woman waved to Junior, beckoning him into her shop, but the boy walked on. He knew she wanted him to reclaim his shoeshine box and get back to work, so he could pay the rent he owed her for sleeping in the back of her shop. He had been avoiding her for several days.

“Hey, Junior! Where you been, kid?” yelled a man from another strip bar doorway. “For a free shine, I’ll sneak you in to see the show.”

Junior just shook his head.

A group of firemen in red windbreakers walked by. The barker spoke more loudly to them. “Show’s just about to start, gentlemen. Only a few more minutes. Lots of firemen already inside. Best strip show on the Block. All the way down. I guarantee it!”

Several of the firemen peeked in and entered as the barker swung the door open wide. “Come on, Junior!” yelled the barker, less loudly. “For a shine, you can see the whole show.”

“Can’t. Lost my box. Somebody stole it. — You got any jobs in there I could do?”

“Depends.” said the barker, looking Junior up and down, with a straight face. “How big are your titties?”

Junior, at first hopeful, was crushed and reddened at the question. He stalked off up the street. “Hey kid! Didn’t mean nothing. Just a joke.” said the barker. “Hell, I could go to jail just for letting you peek in the door, much less work in a joint like this.”

“Ain’t no kid.” yelled Junior, scowling over his shoulder. “And you can shine your own goddamn shoes from now on.”

Junior stopped for a minute at his old corner in the middle of the Block. He looked around expectantly, but there was nothing new or different from the last time he stood in the same spot with his shoeshine box.

A middle-aged man in a black coat, wearing a red top hat and carrying a heavy crate of bottles and boxes sauntered up to Junior. “Hey man, what’s up? You making any money?”

“Doing okay.” lied Junior, with a smirk. “You?”

“We’ll know in a minute. Are you going to stay for the show?”

“Sure, I never miss it when you guys are in town.”

“Thanks, man. We try to be entertaining.”

“Say, Mr. Solomon. Are there any jobs in your show I could do?” asked Junior.

“Let’s see. You’re too small for security. And you ain’t got no tits. Can you do a back flip?” said Solomon seriously, removing his black top coat to reveal a sparkling white tuxedo coat and shiny blue pants. “Can you talk fast? How’s your patter? Mile-a-minute?”

Junior shook his head. “Never done a back flip. But that’s your job, isn’t it?”

“Getting too old for the back flip, man. Almost breaks my balls every time I do it these days. Here, hold my coat. Samson will be here in the middle of the act to get it, okay?”

As Junior nodded, Solomon reached into his inside pocket and pulled out paper money. Junior started to object, but noticed an outstretched hand behind him. Solomon put the money in the hand, and Junior turned to see the young cop pocket a ten-dollar bill. “What are you looking at, kid?” growled the young cop.

“Easy, Bobby, easy. He’s with me. Okay?” said Solomon, signaling to a couple across the street.

The young cop continued to glare at Junior. At once, the man from across the street came over and took the crate from Solomon. With ease, the big man carried it back to the other street corner and swung it to the top of two other identical crates. He took off his own top coat to half cover the top of the crates, revealing a black tuxedo underneath. He placed a large tape player, carried by the woman, on top of the crates and cranked it up to full volume. The woman shed her coat and, barely dressed in a halter top and short pants, began dancing, gyrating wildly in time to the music. The big man used her coat to cover the other half of the crates to form a table. Instantly, a crowd of soldiers and firemen gathered around the dancing woman and the table. “See you later, man.” said Solomon, flattening his top hat and pushing it into a secret pocket in the back of his sparkly white coat. “Sure wish you could do back flips—I’ll think about it and see if there’s a way I can work you into the show.”

Across the street, Samson bellowed, “Ladies and Gentlemen. May I have your attention, please? Presenting, for the first time ever on The Block, for one show only, the Great Magician, Solomon the Wise. With his beautiful assistant, Salome.”

The big man, using just the bulk of his body, cleared a path to the table. At once, Solomon began a run of acrobatic spins and cartwheels, ending in a huge back flip, after which he landed next to the woman beside the table. A small expression of pain escaped his lips, only to be instantly suppressed by a huge smile. Quickly he reached into his coat pocket, popped his top hat and placed it on his head, and began juggling three red, white and blue balls. “Ladies and gentlemen.” he cried. “Welcome. Welcome. And what do we have here.” Solomon stopped juggling and reached into Salome’s cleavage and pulled out a large silver coin. There was instant laughter from the soldiers and firemen who gathered closer to the table. “Yes, ladies and gentlemen, tonight for the very first time ever in New Town, Solomon the Wise. Sponsored by SIN Perfume. Now I need a volunteer from the audience. You, sir?” asked Solomon, pulling a young soldier closer to the table.

For five minutes, Solomon made the silver coin disappear and reappear, turn from two coins to one to none, then reappear out of thin air or out of Salome’s costume. Salome danced and gyrated, following Solomon’s every move. He juggled some more, at one point bouncing balls off Salome’s chest. All at once, he stopped and bowed low, pointed to Salome and she bowed, her breasts spilling from her skimpy top. The audience applauded wildly. Solomon reached over and turned off the tape player.

“Ladies and Gentlemen, SIN Perfume is made from the finest imported aromatic oils and spices, gathered from the great bazaars of the East and the West, and normally sells for eight dollars an ounce.” said Solomon quietly. “But by special arrangement with the manufacturer, we offer it to you here tonight, for one night only, for five dollars a bottle. That’s right! Just five dollars for a three-ounce bottle. That’s a fraction of its real cost, ladies and gentlemen. Now the secret of SIN Perfume is that it’s not only stimulating to men, as my assistant Salome will demonstrate, but it’s also stimulating to women, too.”

Salome took a bottle from Solomon, and applied it generously behind her ears and on her wrists, and in the end onto her breasts, and sashayed through the crowd, preening and fluffing her hair, exaggerating her strut with every step. The crowd murmured excitedly. Across the street, Samson winked at Junior and took Solomon’s coat. The crowd parted as Salome walked and, all at once, she grabbed a young man in a red windbreaker, and began hugging and kissing him, bending her leg around behind him into the air.

At once, Solomon commanded, “Someone stop that woman! She can’t control herself!” Samson went to Salome and the young fireman, and covering her with the coat, picked her up easily and carried her back to the table. “Thank you, Samson.” said Solomon. “As always, ladies and gentlemen, that was a close call. Women just can’t help themselves. Now who’ll be the first to buy SIN perfume?”

The young man in the red windbreaker, the one kissed by Salome, came to the table quickly. “I’ll take two.” he said, and the crowd roared its approval.

Solomon reached into the crates and retrieved two bottles, took the young man’s money in exchange, and yelled, “Next?”

The crowd clamored and jostled each other trying to get to the table to buy perfume. For several minutes, Solomon exchanged bottles for cash. Samson stood close, watching the crowd carefully, still holding onto the girl in the coat. During one lull, Salome broke away from him and yelled, “I’ll take five.”

Instantly the crowd screamed and scrambled and jostled to buy more perfume. Junior laughed. From down the Block, he heard a car horn honking, and looked up to see the young cop directing traffic to detour around the Courthouse. As if from nowhere a squad car appeared with siren and blinking lights. Bobby, the young cop, exchanged a few words with the occupant and moved toward the perfume crowd, blowing his whistle shrilly, “Break it up. Break it up.” he exclaimed between blasts on the whistle. Quickly, the crowd began to disperse.

At once, Solomon handed the tape player to Salome. He and the big man quickly put on the coats from the top of the crates, and Solomon picked up the top crate, considerably lighter than it was a few minutes before. The big man quickly snatched up the other two, and the three walked rapidly away from the young cop. Junior, too, walked away from the scene rapidly.

* * * * * * * *

A few minutes later, from around the dark corner of an alley running deep back behind a large old building, another man called to the boy. “Hey man, where you been? A dude can’t get a decent shine on his shoes ‘round here no more.”

The man was tall and well-dressed, and leaned against the trunk of a shiny luxury car, also hidden in the shadows. “Somebody stole my box, Leon.” said Junior. “I’m out of a job, I guess. You know anybody who needs a good worker?”

“You ain’t old enough to work nowhere around here, man.” said Leon. “Except shining shoes. You better get another shoeshine box.”

“I ain’t going to shine shoes no more, Leon.” said the boy.

Leon stepped around the corner into the light, looking at Junior thoughtfully. “How old are you now anyway, man?” he asked.

“Old enough.”

The tall man laughed. “Old enough for what?”

“For anything. I’m sixteen.”

Leon laughed again. “Maybe so. — I started working myself when I was younger than that. — Over behind the Block.”

“With the queers.” said Junior. “No way.”

“Hey, man, it’s easy work. I could get you started.” said Leon, without emotion. “You just stand around jaw-jacking most of the time. And all that ever happens is you get pushed or pulled for twenty bucks. — Nothing to it. Easiest money you’ll ever make in your life.”

“Twenty dollars?” said Junior, with surprise, as he continued to move away. “No, Leon, I don’t think so. I couldn’t do it.”

“Hell, Junior, that’s eighty shoeshines, man. — You could do real well out there, a good-looking young man like you. Make some real money.”

“No. I couldn’t do it.” said the boy. “I just couldn’t.”

“Don’t have to do nothing. Just stand there and rake in the twenties.” said the tall man. “Come see me later tonight — after things quiet down. I’ll show you. There ain’t nothing to it.”

Junior did not respond, except to walk away a little faster.

“Offer’s only good tonight, man.” yelled Leon, laughing. “It’s now or never, Junior. Now or never, man.”

Junior walked rapidly away up the street, barely able to resist the urge to run. “Bastard.” he said to himself. “Pimp bastard.”

Junior walked toward a thin, three-story theater building, which sat by itself on the corner at the end of the Block. Across the marquee were the words “FAMILY ENTERTAINMENT” with an advertisement for the current double feature. Junior walked to the front of the theater and loitered for a moment, looking at movie posters near the ticket booth. An old woman in a heavy black sweater sat in the ticket-seller’s cage, next to a hand-lettered sign on which the starting times for both movies were crudely printed. Junior went to the window. “What time is it, please, ma’am?” he asked the old woman, looking carefully at the sign.

The old woman lifted her hands from her lap to look at her watch. She was holding a pair of powerful binoculars. “Eight-thirty. Last show starts in a few minutes. You want a ticket?”

“No, ma’am. No, thank you. Ain’t got no money.” said Junior shrugging.

Three firemen walked up to the theater and scanned the posters. “You guys want to see this show?” asked one sober young man in the group.

“Shit.” said a drunken companion. “Can see a fucking movie any time back home. I want to see some fucking pussy, man.”

The third fireman, also drunk, laughed. “Don’t have to go no farther then.” he said, pointing at the sober fireman. “This here’s the biggest pussy you’re going to see tonight.”

“Go to…hell.” said the sober young man, stepping up to the ticket booth. “I’m going to the show. I’ll see you guys later back at the hotel.”

“Not tonight you won’t, pussy.” said the first companion.

The sober young man glared at his drunken friends, bought a ticket, and entered the theater. “So long, pussy.” said the second drunken man.

The two drunken young men threw their arms around each other for support and stumbled back down the street toward the neon signs, laughing together uproariously.

Junior watched the two firemen, as if thinking about following them, but turned and walked the other way, around the corner of the theater building. He paused in the shadows, and looked across the street and down the block at several small groups of teenage boys—some older, but most his age or younger—congregated together in the darkness. An older man walked nearby, stopped, and called a boy over to him. A car crawled by slowly, stopped, and another boy, knowing the driver, ran to the car and got in. The car pulled away from the curb rapidly.

Junior turned his back on the boys. He walked to the side exit door from the theater and tried to pull it open. But it was locked from the inside. Patiently the boy leaned against the wall of the building, waiting.

Across the street and down the block, the older man and one of the boys walked away together in the direction of the Park. From the shadows, another solitary older man appeared and began to walk among the boys.

At that moment the exit door opened and a young couple emerged, giggling. Junior moved quickly and slipped through the open exit door into the theater, sitting down in the first empty seat he found. Many audience members were standing up. When the house lights came up, Junior stood and moved against the crowd to the front of the theater. He sat down in the exact center of the eighth row, his favorite seat. It was the eighth seat in the fifteen-seat row no matter which way you came in. Several minutes later the boy looked around at the sound of the exit door being slammed and locked by an usher. Junior laughed softly to himself. In a few moments the house lights dimmed and the movie began again.

chapter 10: balloonman

As he walked on the narrow street at the back of Park—the night time dead-zone of shops, and stationary stores, and lunch counters that catered to the Courthouse staff during the day, the no-man’s-land that separated the Courthouse from the Block at night—Joey lingered in the deepening eight o’clock shadows, out of reach of the sudden circles of light underneath each lamp post. In one hand he carried a medium-sized, white cardboard box. In the other, he held the strings of a dozen red, white, and blue helium-filled balloons. He had not yet sold a single balloon on this day.

Joey stopped in the shadows near a corner and looked around, up and down and across the narrow street. He was waiting for someone. Across the street in a doorway on the corner, Joey could see a man standing silently, his shiny black military shoes and sharply creased trousers barely visible in the edge of a circle of lamplight, which did not penetrate the inner recesses of the doorway in which he stood. “Mister Charles.” whispered Joey to himself.

Cautiously, Joey moved closer until he could see the man in the doorway more clearly—the heavy black coat and badge, the starched shirt and tie, the glossy leather of the belt and holster, the glint of gun, and the polished brim of the hat pulled low over the eyes. Joey looked hard, but could not tell if the eyes were open or closed. “Evening, Mister Officer Charles, sir.” said Joey, holding up his balloons in greeting.

There was no response from the doorway.

A young couple approached on Joey’s side of the street. Joey watched them—although continuing to look around, searching for someone—but made no effort to sell them a balloon. “I asked what you wanted to do tonight.” said the young man, in an annoyed tone of voice.

“I don’t know.” said the girl. “What do you want to do?”

The young man did not answer.

“Why don’t you buy me a balloon?” said the girl.

“A balloon? What the hell do you want with a balloon?”

“I just want one, that’s all. – Please buy one for me.”

“All right. I’ll buy you a goddamn balloon.”

The young man approached Joey slowly. “Sir? Excuse me?” he said, having a hard time getting Joey’s attention. “How much for one balloon, please?”

Joey stared at him, thinking hard. “One—fifty cents for one.” he said finally.

“Buy two.” said the girl, moving closer. “One for each of us.”

Joey smiled at her, thinking of wine, and put the cardboard box down near the ironwork fence surrounding the Park.

The young man looked at the girl scornfully. “Make that two balloons, please.” he said.

Joey gave the young man two balloons, one red and one white. The man paid with a single dollar bill and returned to the girl hurriedly, handing her both balloons. “Thank you.” she said, childlike, standing unnecessarily on her tiptoes to kiss him on the cheek.

“You’re welcome.” said the young man, mocking her. “Two balloons. – And now we’re just a couple of kids again. Maybe I better take you home. Won’t your Mommy and Daddy be worried about their little girlie?”

“Shut up.” said the girl.

There was a silence until the girl continued, without her previous childlike manner. “What are we going to do tonight?”

“Listen, we ain’t got that many choices.” said the young man. “There’s only three things I ever do with girls. And that’s talk, fuck, and go to the movies.”

“Is that right?” said the girl, without emotion.

There was another silence as the young man stared at the girl, then finally turned away.

The girl broke the silence. “Well, we’ve already been to the movies.” she said.

The young man half turned toward the girl, smiling, and reached out to her. They clasped hands, laughing, and wandered away down the street toward the Park entrance, holding between them the two balloons, one red and one white, that they had just purchased.

Joey muttered and mumbled to himself, alternately looking happily at the dollar bill, then sadly down at the sidewalk. He heard a metallic, clanking sound and quickly pocketed the money inside his coat. He threw up his hand as another old man, dressed in dirty, second-hand work clothes and a ragged work cap, came up the street, pedaling rapidly on a noisy, rattling old bicycle. The old man stood, pushing back and down on the pedals, braking the bicycle, and stopped in the street in front of Joey. “Did you see me?” yelled the old man, out of breath. “I come as fast as I could, but this old bike she don’t go so fast no more.”

“I saw you.”

“How you doing, Joey?”

“Worrying along. How you doing, Rusty?”

“No, I mean balloons? How are you doing with balloons selling?” said Rusty, laying the bike in the street, up against the curb.

Joey did not answer, and Rusty remembered his manners. “Fine. I’m fine.” said Rusty. “Worked all evening mowing that whole big lawn around the church for Mister Wilson. Just now got away from him.”

“Did you cussed him?”

“You know I cussed him. Cussed him up and down and all over that grass.” said Rusty, holding his hands in front of him as if mowing. “But he never heard me. I waited till he went back in the church.”

Joey smiled. “You getting smart, Rusty. If he fire you again, maybe we can’t get him to take you back.”

“Don’t worry, Joey. He fire me again I’ll say ‘Listen here, Mister Wilson, you can’t fire me. I’ve been here longer than you. I got senior-ority. – Now you get back in that church, and don’t let me catch you beating your meat on the back pew again. Or I’ll tell the Big Man, and your dick’ll shrivel up like a pickle.”

“No, Rusty.” said Joey softly.

But Rusty continued excitedly. “I’ll say, ‘You get out there, Wilson, and mow that grass. And bring me a cold beer while you’re up, and don’t drink out of it with your monkey lips.”

“Rusty.” said Joey severely.

Rusty pushed his lips out from his teeth with his tongue, imitating a monkey. He squatted, leaning on his fists, then scratched his belly and arms, and yelled. “You get out there, Monkey-Lips, and mow that grass.”

Joey was annoyed. “Mister Charles across the street.” he said abruptly.

“Where?” said Rusty, suddenly quieter, looking around, finally seeing the policeman in the shadows of the doorway. “Why didn’t you say so?” he scolded Joey.

Joey did not answer. Rusty, mumbling under his breath, sneaked peeks across the street, watching the policeman closely. “He’s asleep.” said Rusty finally, in a superior tone.

“Maybe he is. Maybe he ain’t.”

“Don’t matter no way. You sold any balloons?” whispered Rusty.

“Lots!”

“Enough for a bottle yet?”

“No.” said Joey.

“Shit.”

“If we sell these here,” said Joey, pointing at the remaining balloons, “we can use the money for to buy old bad wine.”

“How many more we got to sell?”

Joey looked up, counting, pointing with one finger. Rusty pointed and counted confusedly with him. “Ten.” said Joey, finally. “If we sells all of them, we can get two whole bottles of old bad wine.”

“Can we sell them?” asked Rusty, licking his lips.

“We can sell them.”

“Two bottles.” sang Rusty. “One whole bottle apiece.”

Rusty looked up hesitantly at the sky. “It’s getting late. Maybe might rain. Might even snow. You sure we can sell them?”

“We needs us a sign.” said Joey.

“A sign?”

Joey picked up the white cardboard box and handed it to Rusty. “Tear this up.” he said. “Get me a flat piece of the white side. I got my box of crayons from the Sunday School.”

Rusty turned away from Officer Charles in the doorway, reached into his coat pocket for a small, but razor-sharp jack knife, and quickly cut a side from the box. He looked around carefully, and particularly at Officer Charles, as he put the knife away. “The Big Man’s going to help us get some wine.” he said.

“Soon as we makes us a sign.” sang Joey.

Rusty laughed. “Going to be a wine sign.”

“Going to be a mighty fine wine sign.”

“For some mighty fine old bad wine.”

Both men laughed happily. Joey took the piece of cardboard and, kneeling down at the edge of a circle of lamp light, laid it flat on the sidewalk. From the inner pocket of his coat—the same pocket where the dollar was hidden—he pulled out a small crushed green-and-gold box of eight crayon stubs. He laid the crayons out on the sidewalk side by side and bent over his work. Painfully, with great deliberation and labor, and with slow, careful crayon strokes, changing colors with each letter—his tongue sticking out first one corner, then the other of his mouth—Joey wrote ‘BALON$.50’.

“Pretty.” said Rusty. “All different colors. A rainbow sign.”

“You hold it.” said Joey, getting up and putting his crayons away. “Show it to the peoples that comes by. Peoples in cars, too. Sometimes they ties balloons on their radio things.”

Rusty held the sign in front of him expectantly, then pushed it out at arm’s length, practicing showing it to people, although no one was there. The two men waited for several minutes, but no one came along to see the sign. They stood for a long time, looking around. Finally, they saw a couple walking rapidly toward them on the opposite side of the street. Rusty motioned for Joey to cross the street, but Joey turned his back. Rusty crossed by himself, holding the sign out in front of him toward the rapidly walking couple, a middle-aged man and woman, who were arguing heatedly as they walked. “He was my father.” said the man. “You could have pretended to cry anyway, couldn’t you?”

“Not for that dirty, foul-mouthed old bastard, I couldn’t.” said the woman. “I’m glad he’s dead.”

The man pulled the woman around by the arm and jerked her to a stop, slapping her hard across the face, knocking off her glasses.

“Hey, you folks wants to buy a balloon for fifty cents?” asked Rusty, ignoring the fight, waving the sign at them.

“What?” asked the man, surprised, seeing Rusty for the first time.

Rusty did not respond immediately. He looked from the man to the sobbing woman. “Do you folks wants to buy a balloon?” he asked, after a moment, quietly. “For fifty cents.”

“No, thank you!” said the man coldly, distractedly concerned about his wife almost from the first moment he hit her. He reached for her, but she quickly turned her back.

Rusty turned also, looking for Joey or other customers. He started back across the street. “Wait a minute.” said the man, looking around him, lost, trying to find a familiar landmark, not recognizing the back of the Courthouse in the dark. “Maybe I will buy a balloon. Where am I?”

“Joey, come here.” yelled Rusty. “He wants one!”

Joey hurried across the street, looking at the man shyly.

“Make that two.” said the man, taking a dollar from his wallet. “Got two kids. Bring home just one of something, and you really catch hell. But you guys know that. – I’m sorry.”

The man looked around at his wife, who still had her back to him. She was sobbing uncontrollably. The man gave Joey a dollar and took two balloons, one red and one white. “Is that the Park there? And that must be the Courthouse, right?” he asked, pointing behind him.

Joey and Rusty both nodded. The man carried the balloons back to his wife. “Here, honey.” he said, forcing his way in front of her, trying to give her the balloons. “We’ll take these balloons home to the kids.”

She refused and moved away down the sidewalk with him following her. “You broke my glasses.” she said.

The man walked back and retrieved the broken glasses from the sidewalk, putting them in the side pocket of his coat. “I’m sorry, sweetheart.” he said, running to catch up with her, the balloons bouncing along beside him. “But you shouldn’t have said those things about my father. — We’ll get your glasses fixed tomorrow.”

“How many more?” said Rusty excitedly. “Is that a real dollar? Let me see it.”

“Eight. – Yes, it’s real.” said Joey sadly, looking after the departing couple and over at the doorway where Mr. Charles remained concealed, putting the dollar in his inside coat pocket.

“Only eight more. – And then the wine.” said Rusty.

“Just seven.” said Joey, tiredly. “I always saves one.”

“Saves one?”

“If I didn’t…”

There was a pause. Rusty looked at Joey in alarm. “If you didn’t, what?” he asked.

“If I didn’t saves one — there wouldn’t be no more tomorrow balloons.”

“What do you mean? Why not? — Are you crazy?”

“If I didn’t saves one balloon—wouldn’t be able to sell balloons tomorrow. There wouldn’t be no… — I couldn’t.”

“You mean it’s like a seed maybe. You put down a seed and the grass grows. Or a flower. Or a tree.”

Joey nodded. “Like you puts down a seed. It’s the Daddy… of all my tomorrow balloons.”

“We can still get two bottles?” asked Rusty.

Joey nodded.

Rusty smiled. “Okay. Keep one. Sell seven. Only seven more to go, right?”

Joey nodded again.

There was a silence. Rusty looked around for customers. Joey stared down at the sidewalk distractedly. “Sawed a boy today.” he said finally.

“What?”

“Forget about it.”

“No, what are you talking about?”

“Don’t want to talk about it.” said Joey. “You’ll make fun of me.”

“I won’t make fun of you. Come on—tell it.”

Joey softened, then gave in. “Sawed a boy today. He was such a pretty little boy.”

Rusty softened as well. “A little girl gave me a cup of water today. She lives next door to the church.” said Rusty. “Said she knew I was thirsty. She was watching me work. She was a nice little girl.”

“Just wanted to hold him. Just wanted to hug him maybe.”

“Her mama came out and told her to stay away from nasty, smelly old men. Told her all they want to do is put their hand up under her dress. She got scared. I could tell because of how she looked at me.”

“Such a pretty little boy. Like a son maybe. Like my son.”

“You ain’t got no son.” said Rusty, but added hesitantly. “Do you?”

“Had a son once. Least she said he’s my son. I got a son somewhere.”

“How come I ain’t never seen him then?”

“He’s not here. Went to away with his mother.”

“What was her name?”

“Donna. — She said he was my son. But I don’t…”

“Who, Joey? When? — I don’t remember all that. And I’ve been knowing you for a long time.”

“Skip it. — Was a long time ago. In another place. And besides, she’s dead.”

“She’s dead? How do you know she’s dead?”

“Just knows it. There’s ways of knowing stuff like that. I mean, dreams and things. — He’s alive though—somewhere.”

Rusty looked at Joey, extremely puzzled. “You think you can sell them, Joey?” he said. “I need a bottle real bad. – And sooner is better is what I say. Sooner is better.”

“We can sell them.” said Joey confidently. “There’s ways of knowing things– dreams and stuff. — And besides, we got to.”

From the back of the Park Jesús emerges, lost in thought. “Hey, Jesus!” says Rusty. “Joey said you was dead.”

Jesús nods at Joey and Rusty, without speaking, and walks by them toward the Block. “Nice sign.” he says distractedly, speaking softly back over his shoulder at them.

chapter 11: old town bar

“Hit me again, will you, ma’am.” said Jim to the middle-aged blonde behind the bar. “Bourbon on the rocks.”

The blonde brought the drink. Jim fumbled with his change on the bar, scooping up all but a few dollars and putting it in the side pocket of his coat. He shoved the rest across the bar. “Keep the change. – How far am I from the Block, anyway?” he asked.

“Just a few streets over.” said the blonde, smiling, pocketing the money, pointing vaguely. “Thought maybe you was lost. Don’t get many suits and ties in here. – Even on Saturday night.”

Jim shook his head, looking serious. “It’s not what you think. A friend of mine—actually he’s more of a business partner—asked me to look the place over. ‘Scout the competition’ he called it.” said Jim. “We’re thinking of opening a bar in this area ourselves.”

“Sure, honey, there’s lots of investor types walking around over there looking for a good deal. – But really, you don’t want to open up another bar around here if there’s any way you can get around it.” said the blonde. “What we need around here is a good hardware store. Why don’t you open one of those?”

The salesman laughed and extended his hand. “Okay, that’s all bullshit.” he said, holding her hand too long. “I just want to look at a little… Hell, call me Jim.”

“Lisa.” said the middle-aged blonde, also laughing, but gently removing her hand from his. “Nothing wrong with looking, Jim. If you don’t do nothing but look, it won’t cost much at all. But touching, on the other hand, touching costs money. Touching costs lots of money.”

“Sorry.” said Jim.

“No problem, honey. I own the place—that is, my husband owns the place, but he’s dead. So, I own the place now, I guess. – Worst thing the old man ever did to me. Died and left me everything he owned.” said Lisa. “By the way, it’s for sale, if you really want to buy a bar. Been for sale since the old man died last year. You could get it pretty cheap tonight, too. – One-time offer. No refunds.”

Jim looked around the large, dim room full of tables and chairs, many of them occupied by groups of tired-looking older men drinking whiskey—some still in work clothes, the Saturday clean-up shift from the mills—although several younger men, scrubbed and fresh from the shower, drank beer clustered around a brightly lit pool table on the far side of the room away from the bar. Two waitresses moved through the space efficiently, taking orders, coming back behind the bar themselves to fill them, getting beer or making drinks. At the other end of the bar, several men on stools sat looking at a television set mounted on a shelf over their heads. “You seem to do a good business.” said Jim.

“Business is great.” said Lisa, reaching under the bar for a half-full bottle of beer. “You ain’t a cop, are you?”

“No.” said Jim, laughing. “Why?”

“Didn’t think so.” she said, tilting the bottle up and drinking deeply. “You didn’t see me do that. Bartenders aren’t supposed to drink.”

“Do what?” asked Jim, then repeated. “You seem to do a good business.”

“Business is great. But it’ll break your heart. – Watching these boys. Been watching them almost twenty years. Now the ones that was boys when I started—their sons are starting to come in. It really does. It breaks your heart.”

“Why?” asked Jim.

“Seeing men get used up. See, they start out young and slick like that bunch over there.” she gestured to the pool table, then nodded at the older men at the tables. “And they end up like that—too damn tired to care. – All used up. It breaks your heart.”

“But that’s life.” said Jim. “It’s supposed to be like that.”

“Life sucks.” said Lisa, slugging down her beer. “This bar sucks.’

Jim shrugged.

“And it’s too many headaches. I think maybe I ought to retire while I’m still young enough to enjoy myself.” she smiled coyly. “I am still young. How old do you think I am, Jimmy?”

Mentally, Jim guessed the woman to be his age, forty, but he said quickly. “Thirty-two.”

“Bullshit. Add a few more years.” said Lisa, smiling. “And I know I look it, too. Up all night. Sleep all day. Never see the sun shine. What kind of life is that?”

“You look great.” said Jim.

“Liar.” said the woman, laughing now. “What do you do? — Sell something, I bet. Sell something by the ton to somebody who don’t need a pound of it.”

“That’s right.” said Jim, smiling in spite of himself. “I’ve sold tons and tons of plastic. Don’t know whether the people really needed it or not. SUE—DOUGH. You ever heard of it?”

“No.” said Lisa, pleased with herself, then switching subjects. “But I’m still young.”

“Of course, you are.” agreed Jack. “And I could sell you…”

“Business is great.” said the woman. “But I need to get away. You know, go down south and lay in the sun for a few years. Maybe get married again. God knows my husband should have done it. But he kept putting it off. Just one more good year, he always said.”

“How’d he die?” asked Jim, but noticing the look on her face, added quickly. “I’m sorry. That’s too personal. I shouldn’t have asked.”

“No, it’s all right. You just reminded me of him the way you asked the question.” said Lisa. “His name was Jim, too. Everybody called him Jimmy though. – Worked himself to death. Or drank himself to death. Depends on who’s telling the story. That the thing about owning a bar. — But this place killed him one way or the other. — He always said we’d sell out and go to one of those islands down south. Maybe work. Maybe not. But never own anything like a bar or restaurant or even an ice cream stand ever again.”

“I’m sorry.” said Jim. “My wife used to call me Jimmy sometimes when no one else was around.”

“You got kids?” asked Lisa.

“Two. A boy and a girl. Gloria Anne and James Junior.” said Jim, fishing out his wallet. “But they’re not kids anymore. Almost grown.”

“Gloria Anne. That’s a pretty name. I always wondered what I’d name my kids if I’d had any.”

Jim showed several pictures from his wallet. “Monica picked it. My wife.”

“She’s beautiful. So young and skinny.” said Lisa.

“Old picture.” said Jim. “She doesn’t look like that anymore.”

“Gloria’s a pretty name.” repeated the blonde.

“I wanted to call her Daphne. But Monica asked me how to spell it, and I couldn’t do it. So Monica named her Gloria Anne. Like Gloria to God, you know. Glory. I always liked the name Daphne.”

“It’s nice.” said Lisa. “How do you spell it?”

Jim shrugs.

“Just a joke. – Me and Jimmy couldn’t have kids. He was too old, I guess. Or too tired. – Or too drunk. Once he got me, I don’t think he really wanted me anymore, you know what I mean?”

“I’m sorry.” said Jim, standing unsteadily, stumbling slightly. “I didn’t hear you.”

“Nothing. It was nothing. Sometimes I talk too much.” said Lisa. “Careful now. You get drunk over on the Block, and those girls won’t leave you a cent. Some woman will get all your money for sure.”

Jim laughed uneasily. “Monica’s already got all my money. – No, that’s not true really. – But I’m not carrying too much. Don’t worry about me. Left most of it back in my hotel room. Just carrying a little fun money. Don’t matter what happens to it.”

The woman laughed. “If you don’t see anything you like over there, come back over here. – It’s nice to talk to somebody new for a change. – Come back later. And I’ll buy you a drink.”

“Thanks, no.” said Jim. “I’m not going to stay out too late. Got to get up early in the morning. Going home to the wife and kids.”

“Maybe next trip?”

“Maybe. – Nice to meet you, Lisa.”

“Nice to meet you, too, Jim.”

chapter 12: jesús

“Our Father, which art in Heaven…

Our Father, which aren’t in Heaven…

Hey, Old Man… Jaybird was here.

Hallowed be thy name.

Our Father……. I just want to understand.

You hear me, Old Man? This is the Jaybird talking.

What do you want me to do?

I want to understand.

What the fuck did I do?

Thy Kingdom come; thy Will be done.

God, you must have quit!

Gave your two-thousand years notice and quit.

Before I ever got here.

‘Cause you ain’t around here no more.

On Earth as it is in Heaven.

Greasy, greedy bastard.

Hit the kid. He would have hit him again, too.

But then I would have been looking for my knife.

Before I remembered.

Would have cut that fat sucker’s heart out before I remembered.

Give us this day our daily bread.

Only caught the kid ‘cause somebody else would have caught him next time.

To teach him…not to hurt him. Not to hit him.

And forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us.

Thou shalt not sit at the back of the hot dog stand and try to sneak out the front door without paying.

Thou shalt not steal… stupidly.

Thou shalt not kill… unless the son-of-a-bitch deserves it.

Thou shalt not commit adultery… until you’re old enough.

Until you’re an adult.

That’s a good one. I got to remember that one.

And lead us not into temptation. But deliver us from Evil.

Jaybird was here.

Jesus, God. What do you want from me? I broke all your commandments but one. You want me to break that one, too?

Come on, Goddammit. Get back to work!

For thine is the Kingdom.

Remember the kid. Back in school. Smart aleck kid. The nun said, ‘What do we call God? What’s his other name?’

Smart aleck kid said, ‘Dammit. When my Dad is mad at my Mom, he calls him ‘God dammit’. The nun sent him to the priest. Remember.

Greedy bastard. Greasy, greedy pig bastard.

Go back and cut his throat and watch him die.

And the Power.

Hotel would probably pay me. Brick his stand up and bury him right there in it.

God dammit.

Hey, Old Man!

Get back to work!

And the Glory. Forever and ever.

All right! All right! All right! All right!

Take it easy, okay?

Eternity is here to stay. Is that it, Old Man? Eternity is goddamn here to stay.

AMEN.”

chapter 13: interlude

The hotel bar was more crowded, mostly with laughing men in red windbreaker jackets with white lettering on the back, drinking mugs of beer from communal pitchers. Preacher, the big bartender, looked around at them distastefully, and then looked at his watch. A few minutes later, Rita came into the bar, no longer wearing her furry coat. “You’re late.” said Preacher.

“I’m here now.” said Rita defensively.

Preacher smiled.

“I clocked in on time, but I had to go to the bathroom.” said Rita.

“Anything wrong?”

“No. Just had to go to the bathroom, that’s all. – Boy, you been pumping the beer with both hands, haven’t you?”

“Nothing but. That’s all these bastards drink.” said Preacher. “Listen, you aren’t going to hold last night against me, are you?

“No, that’s not it.”

“These damn firemen don’t do anything like regular people. – That bastard in particular. I think he got elected to something today. He’s over there in the far corner, holding court. Everybody’s calling him ‘Chief’. You stay away from him. I’ll take care of that table.”

“That’s not it, I told you. It’s something else.” said Rita, searching the far corner of the room quickly. “I don’t want to talk about it, okay?”

“Can you help me out again tonight if I need it?”

“No.” said Rita.

“We’ll just forget about last night.”

“I can’t.”

“Sure you can. It won’t happen again, I promise.”

“It’s not last night.”

“It was just a black eye, wasn’t it? Did he do anything else?”

Rita just looked at Preacher and didn’t say anything.

“It wasn’t my fault.” said Preacher softly. “Ninety-nine percent of guys are pretty decent, and I can spot the other one percent ninety-nine percent of the time. I was just wrong about that ‘Chief’ guy last night.”

“It’s not last night. It’s something else.” said Rita.

“What else? Did he do something else?”

“I don’t want to talk about it, goddammit.”

“But you’ll help me out tonight if I need it?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

Rita sighed, recognizing that Preacher would not accept her answer. “It’s just that I might have my own date tonight, okay.” she said finally.

“Who’s the guy? Where’d you meet him?”

“Who wants to know?”

“I’m your friend, Rita. Remember?”

“If you must know… friend. — My husband’s back. Just got finished talking to him in the Park. That’s why I was late.”

“I’m sorry, Rita. I thought it was last night.” said Preacher. “Or something I did. Or didn’t do. Or something the Chief did. Besides the black eye. I didn’t mean to butt into your business. – I’m sorry. I just wanted to help, that’s all.”

“He’s coming over here in a few hours. You can help me then. – Help me remember to be nice to him, okay?”

“Does he know yet?”

“Know what?”

“About the divorce?”

“No. And he’s not going to know. Not from me. He’d go crazy.”

Preacher shrugged. Rita walked to the closest tables, smiling and chatting, checking on the customers. “How you boys doing tonight?” she asked at several tables.

A small fireman stumbled to the bar, carrying an empty pitcher. “Fill ‘er up.” he said to the barman.

Preacher looked at the man disgustedly. “Certainly, sir. Will that be regular or premium?” asked Preacher sarcastically. “Can I check that oil for you, sir? Tires okay?”

“What do you mean?” said the little fireman, suspiciously.

“If you can’t figure it out, I ain’t going to explain it to you. — Shorty.”

The little fireman flinched, but then pretended not to have noticed the insult. “What the hell is there to do in this chickenshit town, anyway?” he asked.

“Most of us just lock ourselves in a room somewhere and watch television. Real good TV here in the City.” said Preacher. “Other guys I know just lock themselves in a room and beat off all day. But that’s probably the same thing you firemen do at home.”

“You trying to give me some shit?” asked the little fireman.

“Me?” said Preacher innocently.

“You better not be. – Where’s my beer.”

“Go sit down.” said Preacher hotly. “The girl will bring it to you. That’s what we pay her for.”

The little fireman turned sulkily and went back to his table, muttering to himself. Preacher smiled, then laughed out loud. “You bastard.” he said softly. “All you fire fighter bastards. Can kiss my ass, and go to hell. – That’s right. Go to hell. They really got a fire for you to put out down there.”